By Jane Hancock

EDITION #10 – What am I learning & why is it important?

Published – 16th October 2019

Jane is the the Assistant Learning Leader in the Learning Diversity Department at Whitefriars College

Terminology

For the purpose of this article:

- The terms ‘autistic’, ‘on the spectrum’ and ‘on the autism spectrum’ are used in accordance with research (Kenny, Hattersley, Molins, Buckley, Povey & Pellicano, 2016) as it suggests a more positive view of autism as being integral to the individual.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder has been used, in line with the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). However, the author prefers the descriptor Autism Spectrum Condition

- All names of students have been changed to protect their privacy

Introduction

Several years ago, I was supporting new year 7 students at their first school swimming sports, when one boy caught my eye. He looked uncomfortable – hunched over, head down, pulling at his hands and muttering to himself. I didn’t know him well but recognised him from Coding Club and knew he was on the autism spectrum. I guessed that he was probably overwhelmed by the noisy crowd, the humidity and the strong smell of chlorine, so I sat down next to him leaving an empty chair between us. He didn’t lift his head when I greeted him, and instead growled I hate this!

I then asked, ‘So, David’, can you explain to me how Pokémon GO works?

(I should add that it was around the time that the iPhone App had captured the imagination of millions across the world)

The transformation was startling and immediate. David straightened up, swung around, looked me in the eye briefly and then, fully focused, launched into a 50-minute animated monologue that took us comfortably, with the help of a few clarifying questions along the way, to the end of the carnival. David’s passion for computer games was an ‘ice-breaker’ and it helped us to connect. From that day on, whenever I saw David in the playground he was noticeably more relaxed with me, and quite often happily engaged in conversation about his latest gaming interest. As time went by, the conversation extended into broader topics.

There is much to learn about teaching students on the autism spectrum and it cannot be covered in this one article. I have focused the article on special interests and how you can work with special interests to increase student learning. (A longer version of this article is available on the Graduate Teacher Learning Series website). It is also hoped that readers will be encouraged to access the rich repository of resources and learning modules from Positive Partnerships (2009) to broaden their understanding of autism.

Understanding Special Interests

It is estimated that 1 in 70 people in Australia have been diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder with 83% being under the age of 25 (Positive Partnerships, 2009b). Autism is a complex, life-long, developmental neurological condition. Students on the autism spectrum have brains that are ‘wired’ differently to the neurotypical population, which affects how they communicate and learn, fit in socially, regulate their emotions, and experience sensory inputs. They perceive the world through a different ‘lens’, which affects the way they process information and experience the world.

It is common for people on the autism spectrum to have one or more special interests. Until recently, the all-consuming special interests of people on the autism spectrum have been described somewhat negatively as ‘restricted’, ‘narrow’, ‘circumscribed’, ‘fixated’ or ‘obsessive’. The term ‘special interest’ has become less favourable in the context of ‘Neurodiversity’ as it suggests a category other than the normal. I have use special interest in this article because it is the term most people recognise. I prefer ‘passions’ or ‘affinities’.

Building on special interests with a strengths based approach

There can be a tendency to focus on the challenging aspects of autistic students, and on what they cannot do. However, by asking ‘what do they like?’ and ‘what are they good at?’, teachers can use strengths to balance out weaknesses. Winter-Messiers (2007) described special interests as ’those passions that capture the mind, heart, time and attention of individuals with [autism], providing the lens through which they view the world’ (p. 141-142). She and her team researched a strength-based model involving the special interests of autistic students. They found that when students engage with their special interests, they can show surprising strengths in areas usually described as deficits in the autism profile (e.g. expressive language, social communication, body language, self-image, emotional regulation, and fine motor skills).

Special Interests are strong motivators for students on the spectrum and are, potentially, a ‘gold mine of drive and passion’ for teachers to tap into (Winters-Messiers, 2007). By using a strength-based model as the basis for lesson planning special interests can act as a bridge for connecting autistic students to their teacher and peers, the curriculum and even to themselves, by providing a coping mechanism or source of enjoyment.

(Adapted from Winter-Messiers, Herr, Wood, Brooks, Gates, Houston & Tingstad, 2007, p. 71)

This model can be demonstrated using the example of David talking about Pokémon GO in the opening vignette:

- Communication (was able to talk fluently about Pokémon GO, remained on topic and answered questions)

- Social (oriented body appropriately, engaged in some eye contact, highly motivated to explain his interest)

- Emotional (became animated, enthusiastic, relaxed and positive)

- Sensory (no longer appeared bothered by the surroundings)

- Executive function (was able to organise his thoughts in a logical sequence to explain the rules).

Suggestions for using special interests to teach students:

The strength-based model provides a structure for considering ways to incorporate special interests into aspects of school-life. It also has applications for non-autistic students, by encouraging teachers to think creatively to find strategies that support different abilities and ways of thinking and learning.

Academic

|

Special Interest |

Activity |

|

Minecraft |

Embed maths problems throughout a Minecraft landscape |

|

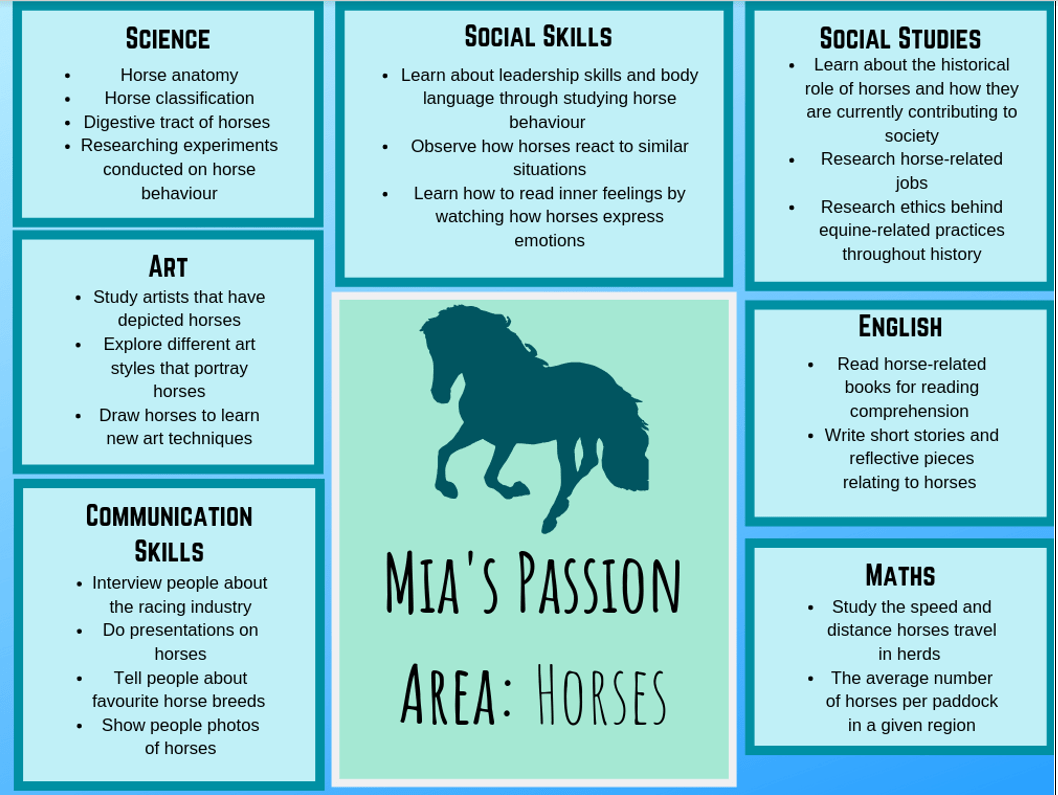

Horses |

Allow student to represent horses using a variety of media (e.g. sketch, pastel, paint, photography, sculpture) then broaden to horses with people, horses in landscapes and other subjects |

|

Dinosaurs |

Include pictures of dinosaurs in worksheets, visual schedules etc. Use judgement- if pictures of dinosaurs are too distracting for some students instead use dinosaur stickers or play-time with dinosaur toys as a reward for completion of school work |

|

Palaeontology |

Create a simple jigsaw using an image of a favourite book – give one piece each time task is completed (maintain motivation by ensuring there are not too many pieces). When puzzle is completed student gets reward of reading time |

|

Transformers |

Have student write a creative story using Transformer characters |

|

Any |

Engaging a student in a conversation around their special interest can indicate academic capability which might not be reflected through assessment tasks |

Communication

|

Special Interest |

Activity |

|

Quantum Physics |

Allow student to be an ‘expert speaker’ or presenter on a preferred topic. Student can use iMovie to pre-record if they lack confidence to speak in front of class |

|

Number Plates |

Have student take photos of teachers standing next to their cars, conduct short interviews with each teacher and then compile into photo-story summary |

|

Drawing |

Some students listen better when they are not looking at the teacher but are drawing – not looking or engaging eye contact does not necessarily mean they are not listening |

Social

|

Special Interest |

Activity |

|

Clubs (Chess, Coding etc) |

Autistic students can socialize in ways that do not look like socializing. They can be in each other’s presence without saying very much and consider that a positive social experience. |

|

Dungeons & Dragons |

Role-playing games can be a safe space to practice social skills with peers who share their interests, and encourage imagination, interaction, listening to others. Having a focus on which to base conversation, creates structure. |

|

Board Games |

Games (e.g. Monopoly, chess etc) can provide a structure for interaction and a requirement for turn-taking. It also provides the opportunity to teach skills in coping with not winning. |

|

Any |

‘VIP of the Week’ allows all students to share their interests. Teaches listening skills and encourages autistic students to ask questions on non-preferred topics. |

Putting it all together – (Example: Secondary student)

NOTE: Sometimes special interests of autistic students become so all-consuming that they inhibit learning or can alienate them from their peers. It is important set clear boundaries. Set time limits on activities involving their special interests, and ensure they take turns. It can be helpful to create visuals that reinforce the rules for students.

Using special interests to address difficulties

Everything is so busy at school and everyone else seems to have a purpose and I never have quite fathomed out what that purpose is. I know we are there to learn but there is so much more going on … It is like beginning a game without knowing any of the rules or passwords’

Luke Jackson (2002, p. 114)

Social/Communication

Social difficulty is a defining trait of autism. As school is a highly social place, it can also be a great source of anxiety for autistic students. It has a ‘hidden curriculum’ that includes all the ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ of society that individuals are assumed to know but are not explicitly taught.

A large number of autistic students have slower processing speeds, particularly auditory processing, which can make fast-moving conversations challenging to decode. Add to that, difficulties reading body language and the fact that idle ‘chit-chat’ tends to be peppered with metaphors, innuendo and jokes which do not translate literally, and it is little wonder that autistic students can get confused. Some autistic students don’t do well with ‘small talk’ and instead prefer to use language for the exchange of facts and information.

When the topic of conversation is their special interest, however, they gain a greater sense of control. They can feel secure in the depth of their knowledge and feel competent. As a result, their fluency of speech, use of body language, level of enthusiasm, expressive gestures, emotion and even eye contact, can all markedly improve. Students who may have appeared shy or reserved under normal circumstances can become animated and eloquent. Interpersonal skills of autistic students can improve when they are able to shine, by sharing their ideas and even teaching their peers.

Stress, Anxiety and Sensory Issues

Much of the anxiety that autistic students typically experience stems from trying to negotiate an environment that is unpredictable and overwhelming. They can have difficulty understanding what is expected of them and what is happening around them. They have problems with planning and organizing and in understanding emotions and abstract concepts. The majority of students on the spectrum exhibit unusual responses to sensory stimuli, particularly auditory and tactile (Positive Partnerships, 2009b). Under stress, the ‘thinking’ part of the brain does not function well, which affects the ability of the student to learn or participate.

In an effort to calm themselves, autistic students may resort to behaviours such as rocking, finger flicking and rituals, or seek refuge in their special interests. When a student’s engagement in their special interest ‘ramps up’ it can be a sign of increasing stress. Special interests can act as thought blockers and provide a safe space for autistics to find comfort, ‘decompress’ and feel happy. When the world around them seems chaotic, the logical process of cataloguing objects and information brings a sense of order that is calming to Autistics. Special interests are far more than hobbies to autistic students and are tightly linked to their self-image; some actually feel they are their special interest, while others describe special interests as being ‘a matter of survival’ and ‘like oxygen’ or a way to feel ‘completely themselves’ and ‘light up inside’ (Cook & Garnett, 2018).

Key takeaways for Graduate Teachers

Autistic students think differently so you must meet them in their ‘space’. Special interests are closely interwoven with their self-image; by honouring those passions you can make an autistic student feel valued which can help you to connect with them.

Collaborate with parents to create a ‘snapshot’ of the student – Positive Partnerships (2009) has an excellent module, ‘An Introduction to the Planning Matrix’ that explains, step by step, how this may be done.

Discussion with your mentor

After reading the article have a chat with your mentor:

- What has your mentor done to adapt lessons and activities to capitalise on special interests?

- How might a ‘strengths-based’ approach benefit all students in the class?

References

American Psychiatric Association 2013, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5TM (5th ed.), Washington DC, Author.

Autism in Australia. (2017, April). Retrieved May, 2018, from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/autism-in-australia/contents/autism

Cook, B & Garnett, M 2018, Spectrum women: Walking to the beat of Autism, London, United Kingdom: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Department of Education, 2019, Disability standards for education 2005, viewed 1 August 2019, https://www.education.gov.au/disability-standards-education-2005

Jackson L 2002, Freaks, geeks and Asperger Syndrome: A user guide to adolescence, London, Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Kenny, L, Hattersley, C, Molins, B, Buckley, C, Povey, C, & Pellicano E 2016, Which terms should be used to describe autism? Perspectives from the UK autism community, Autism, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 442-462.

Positive Partnerships 2009, Positive partnerships, viewed 1 August 2019, https://www.positivepartnerships.com.au/

Winter-Messiers, MA 2007, From tarantulas to toilet brushes: Understanding the special interest areas of children and youth with Asperger Syndrome, Remedial and Special Education, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 140-152.

Winter-Messiers, MA, Herr, CM, Wood, CE, Brooks, AP, Gates, MAM, Houston, TL, Tingstad, KI 2007, How far can Brian ride the Daylight 4449 Express? A strength-based Model of Asperger Syndrome based on special interest areas, Focus on Autism and other Developmental Disabilities, vol. 22 no. 2, pp. 67-79.