By Tanya Whiteside

EDITION #8 – How can my students & colleagues help me to be a great teacher?

Published – 21st August 2019

Tanya Whiteside teaches at Berwick Fields Primary School and Swinburne University

Developing responsible learners

‘We were convinced that any change in student learning would be directly linked to a similar change in our teaching practice’ (Osler & Flack, 2008, p.6).

At the heart of developing responsible learners is the teacher. Over the years I have come to realise that examining what I do as the teacher, first and foremost, is a critical element in how I expect my students to behave. In supporting my students to take responsibility for their learning, there are specific and explicit things that I can do on a daily basis to enable this. It doesn’t happen by chance, nor does it happen overnight. It takes effort and persistence by the teacher for independent learning to evolve.

Background

From my very first term of teaching I have invested time and effort into supporting my students to be responsible learners, who can make great decisions for themselves and work independently. In fact, my Victorian Institute of Teaching (VIT) focus for my full registration was centred on supporting my Foundation students to make their own decisions. I did this through the year level inquiry topic which was on ‘Nursery Rhymes’. In everything we did during that inquiry I kept coming back to my learning agenda. I focused on running a content agenda alongside a learning agenda (I explain the difference between these two terms in the section on structuring lessons below). In this case we were not only learning nursery rhymes and all that entails but also learning to be responsible and independent learners.

I have been inspired by the work of the Project for Enhancing Effective Learning (PEEL). This project began in a secondary school in Melbourne in 1985 as a two-year collaborative action research project. A group was formed comprising teachers and academics who focused solely on aspects of quality teaching and learning. At that time, 34 years ago, it was an innovative and ground-breaking project. When the participants reflected on their practice they realised there were many behaviours that their students were exhibiting which they were concerned about; passive learning, unreflective learners, learned helplessness, and dependence on the teacher. They saw these tendencies as habits that could be learned and unlearned and that students could learn how to learn better. The teachers met on a weekly basis to discuss what they were seeing and over time generated a list of ‘Good Learning Behaviours’ that they aimed to teach to their students in order to develop responsible and independent learners. Important in this work was the role of the teacher as a co-constructor of knowledge.

The Journey

Supporting students to take responsibility for their learning is a journey and should be seen as a year-long goal. It begins from day one and needs to be taught explicitly. We take for granted that students come to us knowing what to do if their pencil is blunt or if they have lost their scissors. We often assume students know what to do if they are stuck, confused or unsure. As with everything in my practice, I have found that building a strong connection with my students is essential to me being able to support, encourage and influence their actions. If they do not trust me or can’t connect with me, demonstrating responsibility for their own actions is going to be a stretch for me to teach and for them to learn. In the words of inspirational educator Rita Pearson ‘kids don’t learn from people they don’t like’ (TED Talks, 2013).

Using the High Impact Teaching Strategies (HITS)

The High Impact Teaching Strategies (Department of Education and Training, 2018) provide a structure for the way that teaching, and learning can be approached. When supporting students to be responsible learners we need to ensure we are:

- setting goals with our students based on our observations

- structuring lessons to enable learning skills to be a focus

- explicitly teaching what being responsible looks like, sounds like and feels like

- working in collaboration with each other (students and teachers)

- exposing students to the skills we want to see in multiple ways

- giving feedback and opportunities along the way to provoke students to think metacognitively about their own learning

Setting goals

Having a goal in mind to start with is important because we cannot change everything in our classroom all at once. We need to observe and decide on what behaviours we want to target first. Discussing concerns or observations with the students allows their voice to become part of it. As the teacher you should ask yourself, ‘what is concerning me the most about the day to day behaviours I am seeing?’ Is it the way the students ask you questions that they can work out for themselves? Is it the way they are staying stuck with certain tasks? Is it the lack of contribution they make to class discussions? Pinpointing one aspect to start with is the key. When I facilitated the PEEL group at my school, one of the Foundation teachers set a goal of supporting her children to know where everything was in the classroom in an effort to help them become more responsible. This emerged from her concern about glue sticks. The students were not putting the lids back on after using them and did not know where they were kept in the classroom. Resources were being wasted and valuable learning time was used up in searching for materials. Think small steps. Share the goal you have chosen with your students, so that everyone knows what the class is working towards. Collaboration is key.

Structuring lessons

I structure lessons so that they include a learning agenda running alongside a content agenda. The learning agenda is the skills I want the students to focus on in any given lesson, for example, thinking, decision making, team work, growing their mindset. The content is the specific reading, writing, mathematics, science, history, and so forth that I want them to learn. When students know I am looking for learners who are ‘on task’ or who are ‘not staying stuck’ they can focus on those skills while learning to read or write. Over time it becomes second nature to make a link, do an enviro walk, or ask a question when you are stuck. Running a learning agenda alongside the content agenda works: “Today we are learning to recognise 3D shapes as well as how to work in a team and make decisions.”

Explicit teaching and multiple exposures

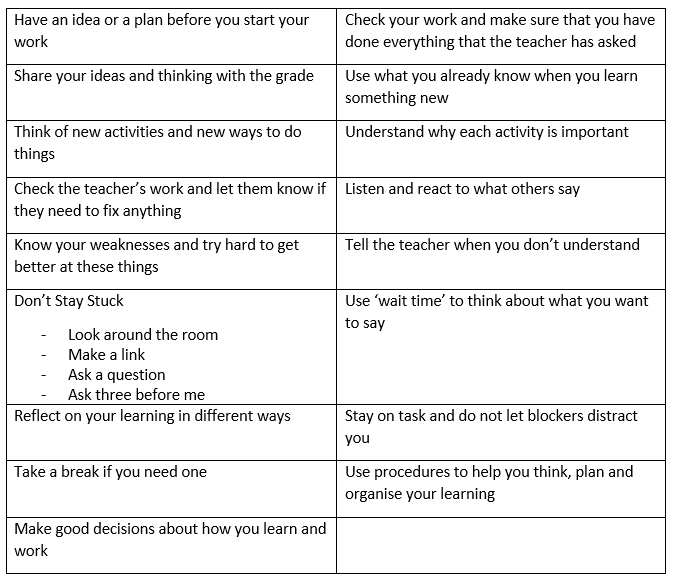

I explicitly teach learning concepts to my students through class discussions, role playing, Circle Time sessions, learning intentions and morning meetings. I set aside time to teach the Good Learning Behaviours (GLB’s) (refer to Table 1). Sometimes this might be a ten minute discussion, at other times it might be a one hour long session. I usually start with the GLB ‘Don’t Stay Stuck’ and spend time unpacking what this means, because usually on day one of a new year I am bombarded with questions that could be answered easily or learners who are passive in their approach to tasks. I introduce the GLB’s as I see the need arise in my classroom.

There are 17 GLB’s generated from a primary perspective which also apply to secondary students. In any given year I don’t teach all of these; I teach the ones that are most relevant to my learners that year. I either stop the class and introduce what is needed in the moment, or I plan for a session once I see something of concern, or I plan to introduce a new one at the start of each week. Part of this is me as the teacher knowing the GLB’s explicitly and knowing when I am seeing them in action (or not). In implementing something like this the teacher’s behaviour must change to be able to name and notice the actions necessary for instilling responsibly in students. The GLB’s become my language for learning and I use the language and expose my students to it throughout each day.

I combine the GLB’s with the ideas of Carol Dweck (2006) and her work on mindset as well as the ideas of James Nottingham (2010). When combined, this has given my students a supportive structure to become responsible and independent learners.

Table 1: Good Learning Behaviours – An extended list incorporating the work of Flack et al (1998) and Whiteside (2010)

Working in collaboration with students

Once a goal is set up with my students, I want to work with them to achieve it. I am a co-constructor of learning. If they are having a hard time developing, for example, their mindset or their ability to take on challenges, I think about what I can do better to help them. I don’t ever blame my students. I seek to understand my own behaviours. I support the students with ways to monitor the goal.

Developing metacognition through feedback

If we can foster reflection and metacognition as part of our year long journey we have done well. If we can guide our students well enough to be able to not only think about their own learning but to also be able to articulate what they are thinking, we are developing strong and thoughtful learners.

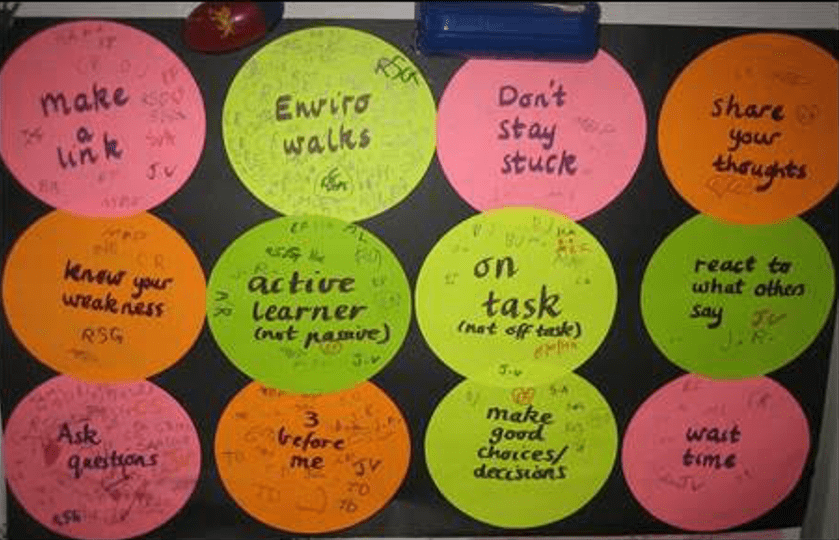

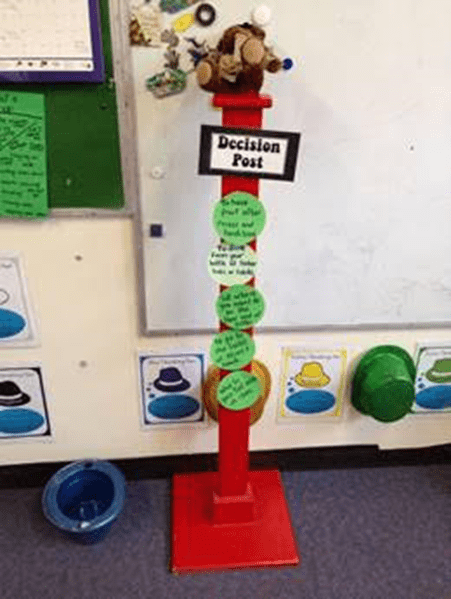

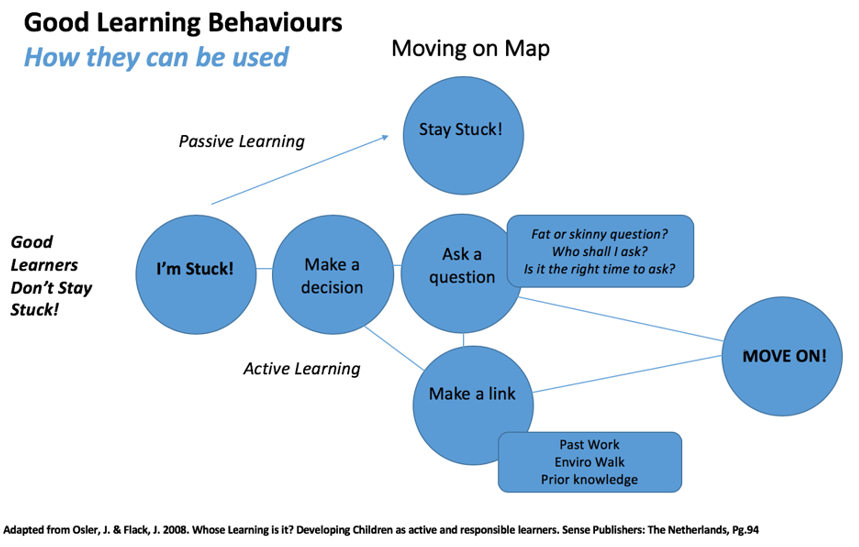

I catch students who are enacting the behaviours of responsible learners and I stop the class and celebrate it. I give them feedback constantly on what I see and why this was important to them as a learner. This leads to students being active in ‘catching’ themselves or each other demonstrating the GLB’s. They start to take responsibility for their learning. Soon everyone wants to be a good learner and it becomes intrinsic. I set up structures to help the achievement of GLB’s such as decision posts, moving on maps or feedback stations (Osler & Flack, 2008). Some examples are below.

This image is of the students ‘catching themselves’ as good learners. They initial this chart when they catch themselves. We can then see what we need to work on as a class and set further goals.

These are images of my Decision Post. As decisions are handed over to the students they are put up on the post. Once they are on the post students have the responsibility to make these for themselves. Having a ‘Decision Wall’ somewhere in the classroom can work well too if you don’t have a physical post!

This is an example of a ‘Moving on Map’

When we see learners who will take risks, who are open to challenges and making mistakes, and who want to be the best they can be for themselves, we are supporting them to be responsible learners. Regular discussion is important and as Mitchell et al. (2009, p. 203) state, ‘this act of regularly talking with students about learning is a key aspect of learning how to learn, or metacognition’.

Challenges

It takes time to develop a culture of responsible learners and we should see it as at least a year long journey. We need to use our shared language for learning through everything we do and teach. It needs to become embedded so that it is just the way we work.

It is important not to fall into the trap of declaring, ‘I taught my class what to do when they are stuck but they are still getting stuck’. We need to seek to understand why what we have taught is not working. We need to self-question:

- Have I only introduced this concept and not referred to this again?

- Do I know the behaviours I want to see well enough to catch them in action?

- Do I have a goal in mind?

- Am I teaching my students to be responsible by explicitly teaching the skills and then giving them opportunities to practise these each day?

Seeing this as important work will make it a priority.

A key takeaway

Explicitly teach your students how to be strong, active, independent and responsible learners. Don’t assume they know how to do this or will be able to do this after just one lesson. Develop a shared language in your classroom around learning behaviours you wish to see. From this language actions will follow. A defining factor that transforms practice is the involvement with other teachers through regular discussions. Work out what the main focus needs to be and start small. Big things will grow.

Discussion with your mentor

As hard as it can be even for the most experienced teachers, seek to identify what you need to change about your own teacher behaviour in an effort to develop responsible learners. Every time I have had an issue in my classroom I have found that looking directly at my own actions has been helpful. Questions that you might discuss with your mentor include (these could be good questions for a classroom visit by your mentor):

- What am I doing to enable or inhibit responsibility to take place?

- Am I behaving the way I want my students to behave?

As Guy Claxton (2008) advocates, ‘If we want young people to develop the habits of thinking for themselves, using their imagination, being open to new ideas, saying when they don’t understand, and exploring real challenges together, then they have to see their teachers doing the same thing’ (p. 123).

References

Claxton, G. 2008, What’s the point of school? Rediscovering the Heart of Education, Oneworld Publications, United Kingdom.

Department of Education and Training. 2017, High impact teaching strategies: Excellence in teaching and learning, viewed 31 May 2019, http://www.education.vic.gov.au/Documents/school/teachers/support/highimpactteachstrat.pdf

Dweck, C. 2006, Mindset: The new psychology of success, Random House USA Inc, New York.

Mitchell, I., Mitchell, J. & Lumb, D. 2009, Principles of teaching for effective learning: The voice of the teacher, PEEL Publishing, Victoria.

Nottingham, J. 2010, Challenging learning, Routledge, London.

Osler, J. & Flack, J. 2008, Whose learning is it? Developing children as active and responsible learners, Sense Publishers, Rotterdam.

Flack, J., Mariniello, S., Osler, J., Saffin, A. & Strapp, K. 1998, PEEL from a primary perspective, PEEL Publishing, Victoria.

TED Talks, 2013, Every kid needs a champion: Rita Pierson, viewed 31 May 2019, https://www.ted.com/talks/rita_pierson_every_kid_needs_a_champion?language=en

Whiteside, T. 2010, Thinking through play, Masters thesis, Monash University, Melbourne.